Did you know the National Health Service has historic links with another service that runs on critical workers – the railway?

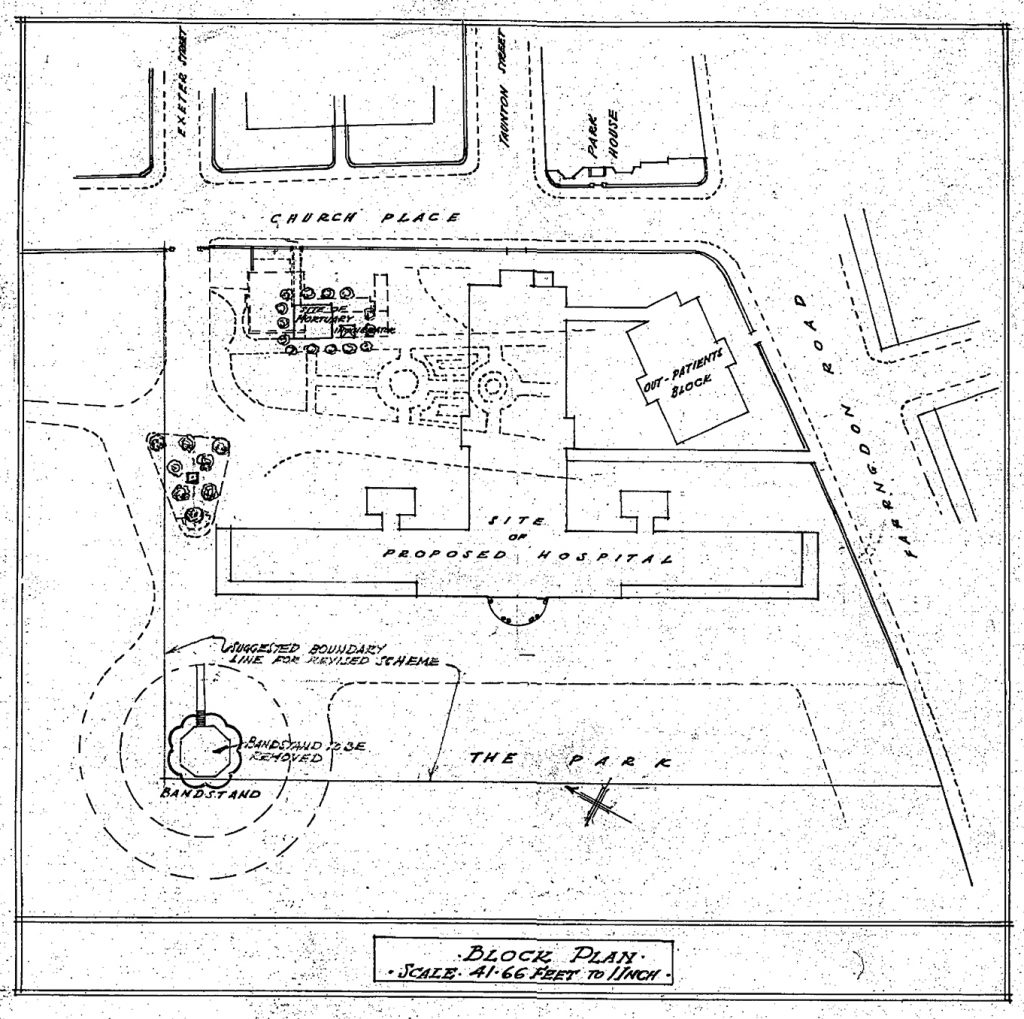

Take a stroll down Swindon’s Faringdon Road and you might spot a spot a blue plaque commemorating the role of the Great Western Railway’s former medical fund and baths building as “the blueprint for the NHS”.

The GWR – Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s link between London Paddington, South West England and South Wales – chose Swindon for its locomotive works in the 1840s. In 1847, the railway company founded The Great Western Railway Medical Fund Society to help look after its workers living in the GWR New Swindon railway village, according to Historic England.

It came after Daniel Gooch, superintendent and a friend of Brunel, grew more concerned about accidents and epidemics affecting the staff. He sought permission from the company’s directors to launch a fund that would improve their health, boost reliability and encourage skilled workers to remain with the GWR.

The company deducted money from employees’ wages to fund the society, initially called the Sick Club, and in its early days provided a doctor who staff and their families could see for no extra cost.

The railway works got bigger and so did the fund’s provisions, which later included a swimming pool, baths and eventually Turkish baths.

In 1871, the fund opened a cottage hospital, which offered accident and emergency services for staff and, from 1887, a dental practice at the Mechanics’ Institute.

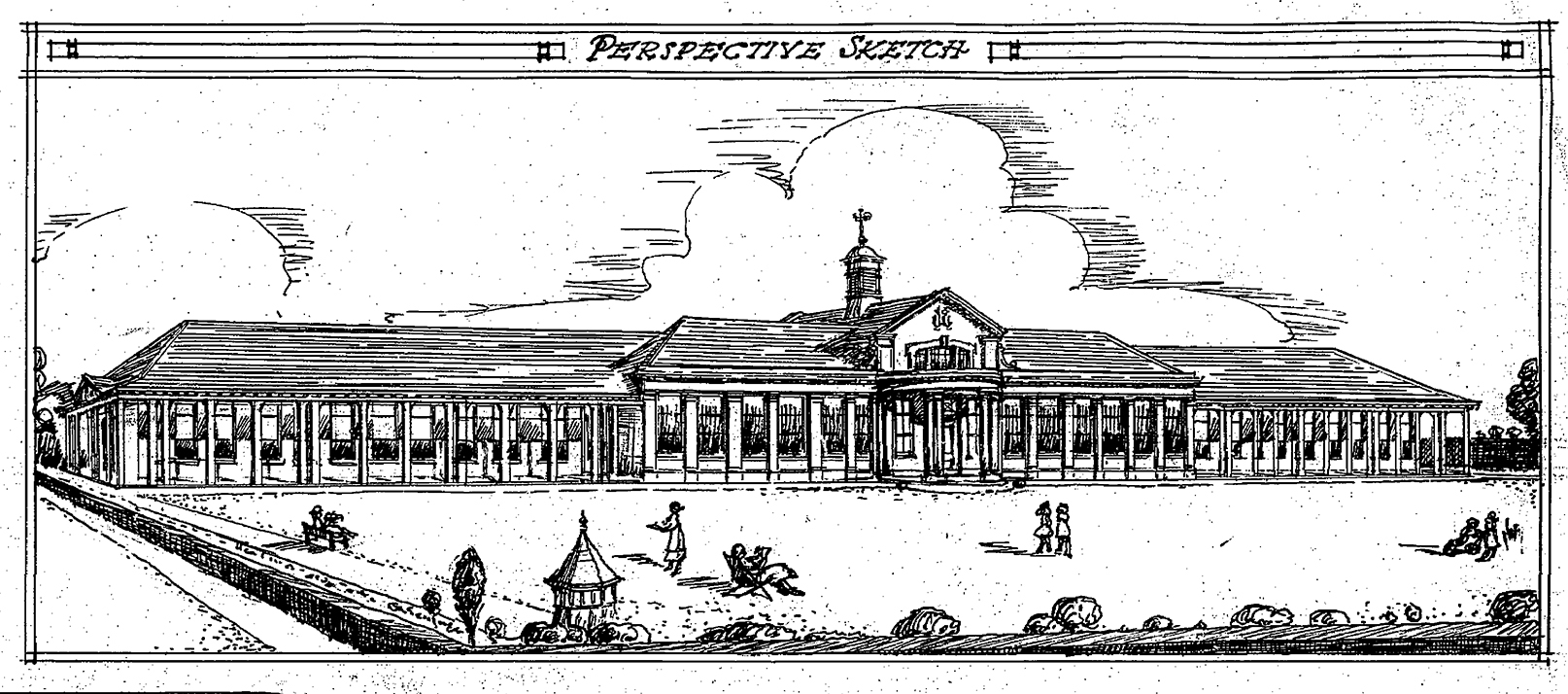

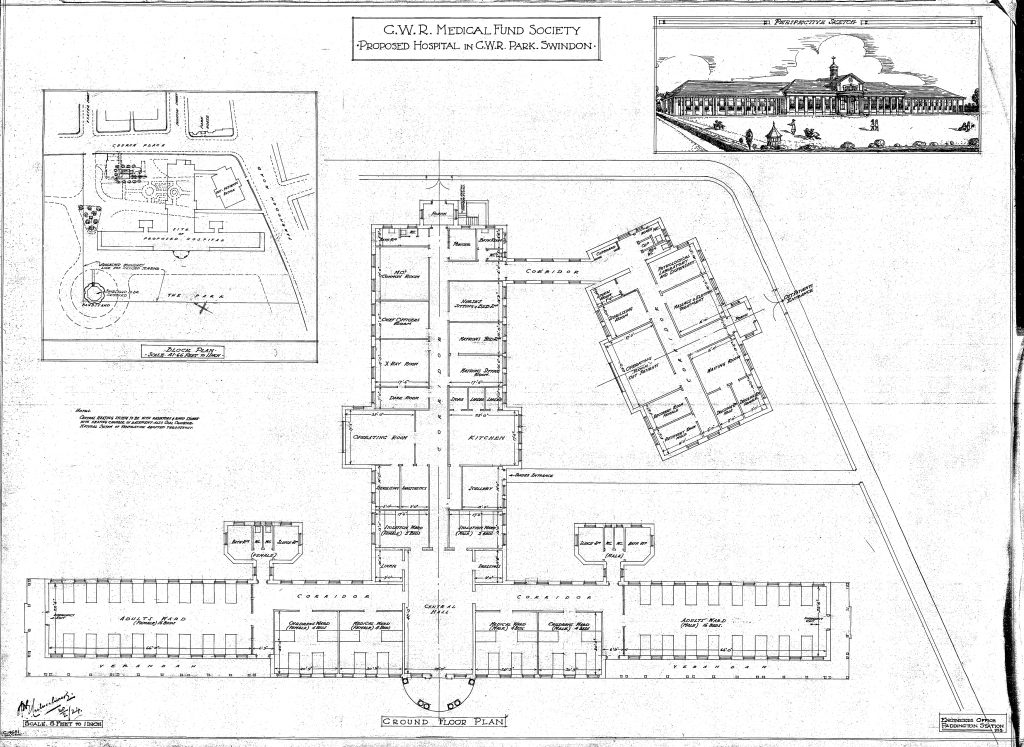

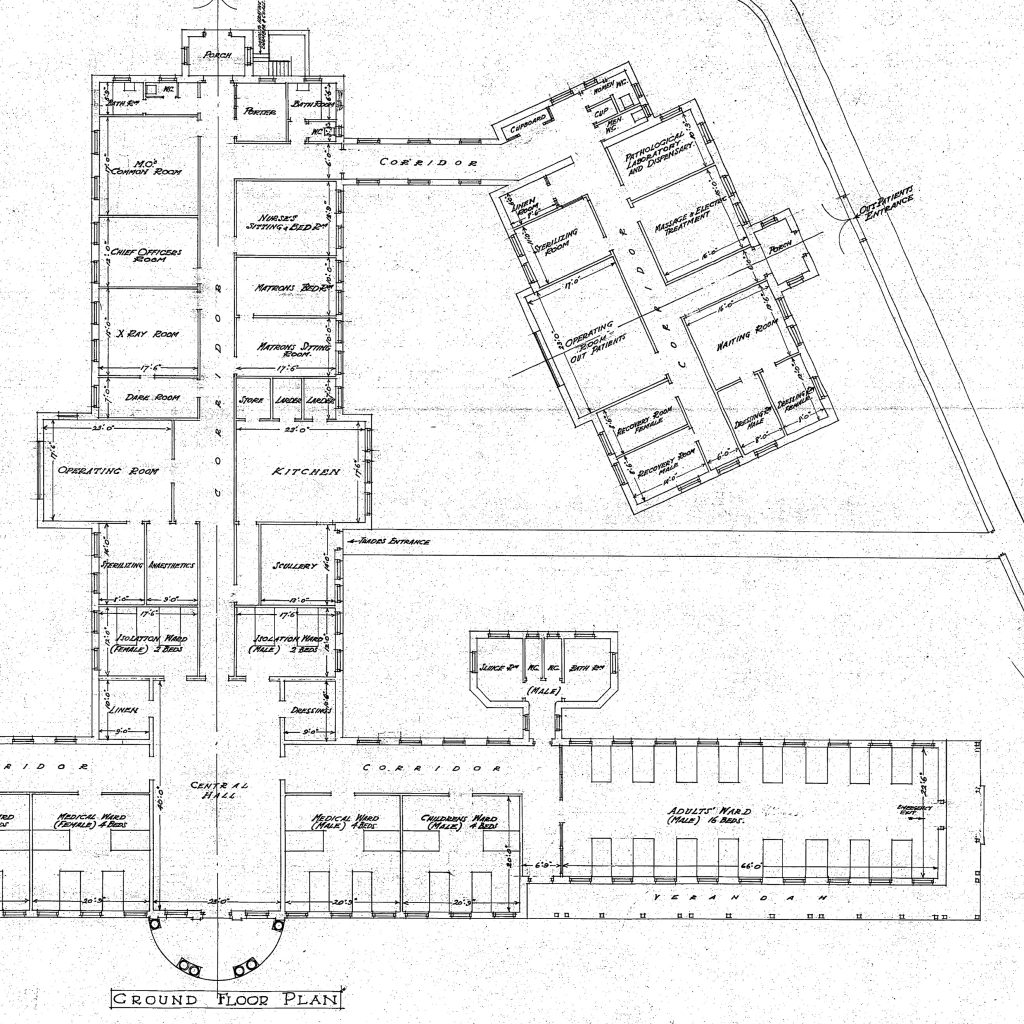

The first of the present buildings on Faringdon Road were built between 1891 and 1892 to bring the society’s services under one roof. The dispensary, consulting rooms and waiting room occupied a site on the corner of Milton Road. A tunnel at basement level beneath the main entrance went north, under railway village’s houses and straight to the carriage works, allowing the transport of supplies including coal.

Bevan’s stamp of approval

The fund wound up as the NHS reached the planning stage and was officially established in 1948. By then, the fund’s Faringdon Road site comprised swimming baths, Russian and Turkish washing baths, a dispensary, a doctor’s, dental practices and laboratory, and specialist medical departments.

After politician and NHS champion Aneurin Bevan visited the facilities, he said: “There it was, a complete health service. All we had to do was to expand it to embrace the whole country.”

The London, Midland and Scottish Railway also had a hospital, on Mill Street in Crewe. According to ‘Crewe: Railway Town, Company and People 1840 – 1914’ by DK Drummond, the Grand Junction Railway, 2as paternalistic creator of New Crewe, the GJR Company,” built “a series of railway hospitals… The earliest being situated on Liverpool Terrace right beside the mainline, while the most recent, Mill Street hospital, was purpose built early in the present century”.

The Architecture the Railways Built – Great Western Railway

Florence Nightingale’s 200th birthday – a nursing pioneer’s links with Brunel

Integrated infrastructure

Swindon and Crewe are not the only home to historic railway connections with Britain’s healthcare system.

John Page, a records assistant at Network Rail’s archive, said: “It was very common for hospitals, especially those for mentally ill patients, to have railway connections. These were not only used for patients but were crucial for goods, like coal, and food.

“Usually these hospitals were built in remote areas to keep patients isolated from the general public, so, in a time when roads were not the most efficient way to move goods, the railways allowed connections to their network.”

They included Hellingly Hospital, a large psychiatric facility near the village of Hellingly, east of Hailsham, which had its own electric tramway, the Hellingly Hospital Railway, according to the NHS.

It was built in the early 1900s to help relieve overcrowding at the Haywards Health Asylum, formerly the Sussex County Asylum.

It had its own electric tramway, known as the Hellingly Hospital Railway. The line went from Hellingly railway station to the hospital’s boiler house and primarily helped transport coal for the boiler system and electricity plant.

Other healthcare facilities with their own railways included Hartwood Hospital in Shotts, Scotland, which had its own railway connection to the station, and High Royds Hospital Railway; Horton Light Railway; St Edwards Hospital Tramway and Whittingham Hospital Railway.

Read more:

Film: Discover the Network Rail archive

The Architecture the Railways Built – Severn Bridge Junction

The Architecture the Railways Built – London St Pancras International

The Architecture the Railways Built – Ffestiniog Railway

The Architecture the Railways Built – Ribblehead Viaduct

Isambard Kingdom Brunel and the Great Western Railway

Preserving railway history: five things saved by Network Rail