Exceptional images have re-emerged of one of Kent’s biggest landslips, highlighting the essential work by Network Rail to maintain coast-side railway lines.

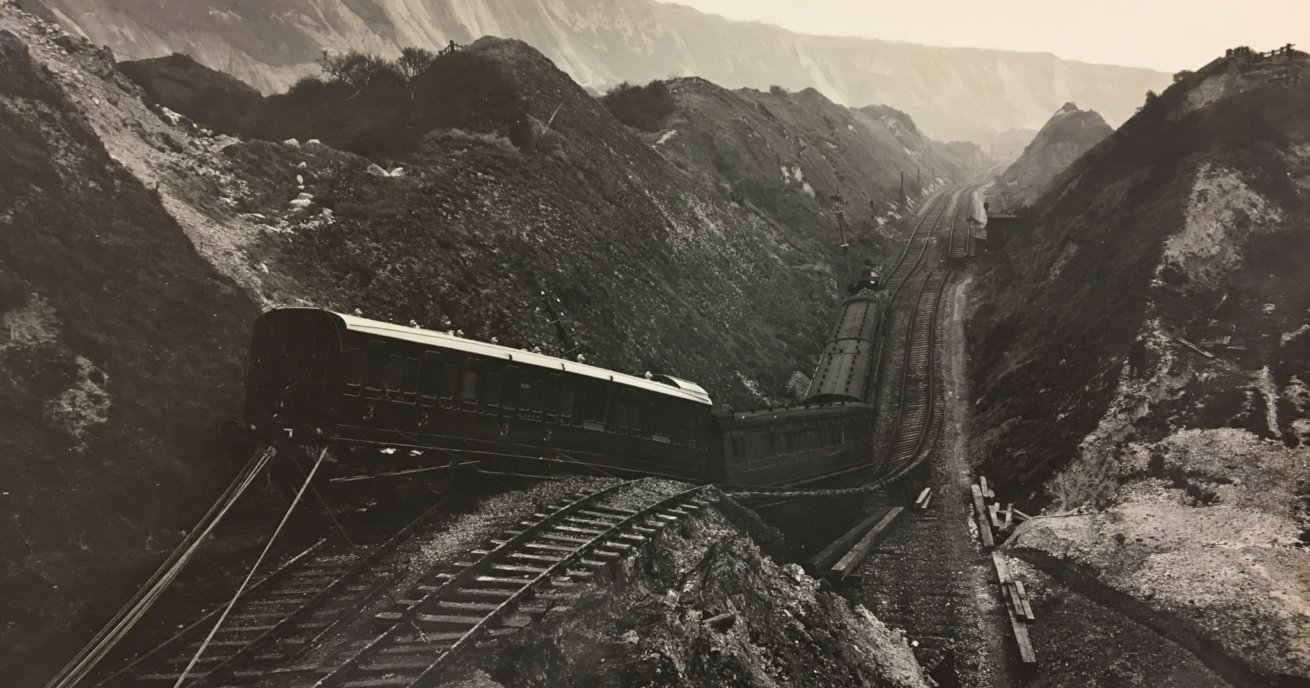

Original photographs of The Great Fall, a severe landslip at Folkestone Warren in December 1915, show train derailments and continued rail movement following the incident.

The railway line to Dover moved 50 metres towards the coastline and 1.5 million cubic metres of chalk fell into the sea following weeks of heavy rain.

The line remained closed until 11 August 1919, the First World War having delayed its reopening.

Click on the gallery to see more images

Derek Butcher, a route asset manager at Network Rail, found the historic images in a filing cabinet while moving offices.

He said: “All landslides are activated by rainfall… [that location] has quite complex geology formed of chalk overlying clay. The water from the rainfall percolates through the chalk and sits on top of the clay and saturates it, and leads to landslips. The chalk can’t sit in a stable manner on the clay when it’s that wet.”

The kink in the line remains visible today, underscoring the severity of the incident.

Click on the gallery to see more images

Derek said: “We believe the train pictured was alerted to the landslip by the signal box at Folkestone Junction and was slowed down and found itself part on and part off the landslip. They were able to evacuate passengers who walked through the tunnel to Folkestone Junction station.

“There was a significant amount of movement following the train stopping… That’s why it looks so horrific.”

Landslips have been a major feature of the line since it opened in 1844. In 1877, two people died when part of the Martello Tunnel was destroyed. The line remained closed for three months afterwards.

The last major movement was recorded in 1939 but Derek said some ground movement had forced Network Rail to implement speed restrictions on the line in recent years. The need to take such precautions typically follows a very wet winter.

Landslides can occur anywhere and when they impact on railways, roads and other infrastructure, they can cause a lot of disruption.

As the earth becomes heavier, the water forces apart grains of soil so that they no longer lock together – resulting in a landslip as the structure becomes loose and unstable.

Derek said: “The landslip [at Folkestone Warren] is still active… There are a number of ways that movement is controlled. Firstly, we monitor the location extensively with settlement points on a monthly basis.”

We also use light-detecting and ranging (LIDAR) technology, a laser scanning technique to record points on the landscape. The data helps us keep track of which locations are moving.

Other techniques include boring holes in the ground to drain water, and building walls and other structures designed to stop the landslip from moving.

Meanwhile, Derek and his team regularly walk over locations at risk, comparing photographs to see whether the ground has moved.

Nearby, Network Rail has responded to another major incident caused by severe weather in recent years. In March last year, Channel swimmers joined Network Rail to celebrate reopening of Shakespeare Beach in Dover following a huge project to rebuild the sea wall protecting the railway between Dover and Folkestone. The wall had suffered significant damage after the storm of Christmas 2015.

Repairs began in January 2016, when the first of 90,000 tonnes of granite rock armour arrived on site. Network Rail engineers worked to place the rock armour along the wall and install a new footbridge across the railway and down to the beach.

The railway and sea wall itself were opened in September 2016.