It’s the final stop for television presenter Tim Dunn on his exploration of the incredible architecture on the railways across the UK and Europe.

Watch the last episode of his 10-part series, The Architecture the Railways Built, on Yesterday for a journey on the Great Western Railway – a legacy of Isambard Kingdom Brunel and electrified along much of the line for faster and more frequent services.

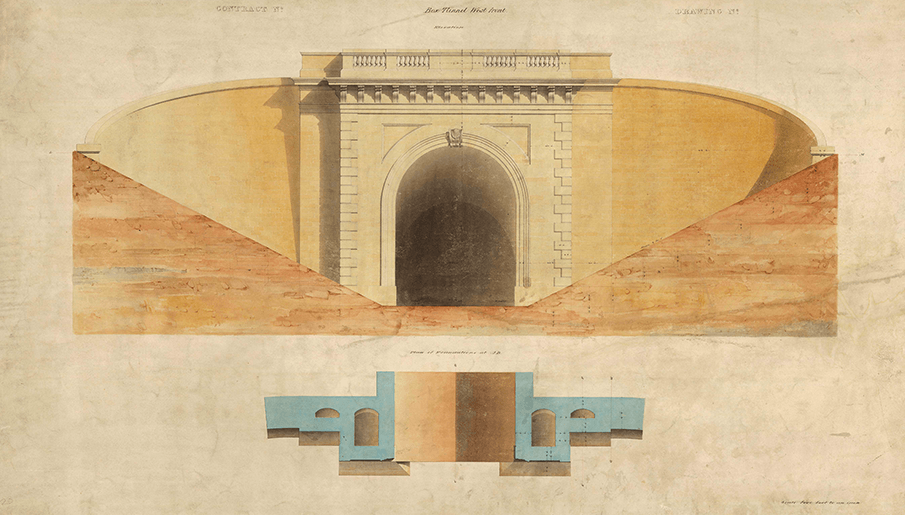

This 116-mile route from London to Bristol opened on 30 June 1841 after work began in 1836. It was Brunel’s vision to link London and New York via Bristol by train and steamship but building the railway line was much more difficult, expensive and time-consuming than he had estimated. The huge work needed to build the Box Tunnel near Bath was especially to blame; it delayed the completion of the line – by August 1839 only 40% of the tunnel had been constructed.

In January 1841, Brunel persuaded his major contractor to increase his workforce from 1,200 to 4,000 men to finish most of the tunnel in April 1841.

Work on the tunnel had begun from the east and west sides of Box Hill in 1836; Brunel’s calculations, and the skills of the contractors and navvies were such that when the two ends met in 1841, the difference in their alignment was less than two inches (5cm). It opened to through London – Bristol traffic on 30 June 1841, without ceremony.

Shareholders, particularly in Liverpool, were dissatisfied with Brunel and unsuccessfully tried to remove him from office before the line completed. His robust defence of the engineering on the line secured his position but debate raged about his use of the broad gauge rather than rival engineer George Stephenson’s ‘standard gauge’ of 4ft 8 1/2 in between the rails, which became commonplace.

Read more about the Box Tunnel here.

SS Great Western

The Great Western Railway established the Great Western Steamship Company to promote the London to New York venture and appointed Brunel as its chief engineer.

His first ship for the company, the SS Great Western, was the largest steamship of its day. It was big enough to carry the fuel needed to power the journey and established non-stop steam navigation across the Atlantic on its maiden voyage in 1838.

His second ship for the company, the SS Great Britain was even bigger and the first large ship to be built of iron.

However, it was the SS Great Eastern that became Brunel’s biggest ship building challenge. Designed on a massive scale her construction and eventual launch in 1858 were fraught with difficulties. A ship on this scale in the mid nineteenth century was not a commercial success, but was the forerunner of the cargo ships commonplace today.

The Architecture the Railways Built – Severn Bridge Junction

The Architecture the Railways Built – London St Pancras International

The Architecture the Railways Built – Ffestiniog Railway

The Architecture the Railways Built – Ribblehead Viaduct

A modern route for faster services

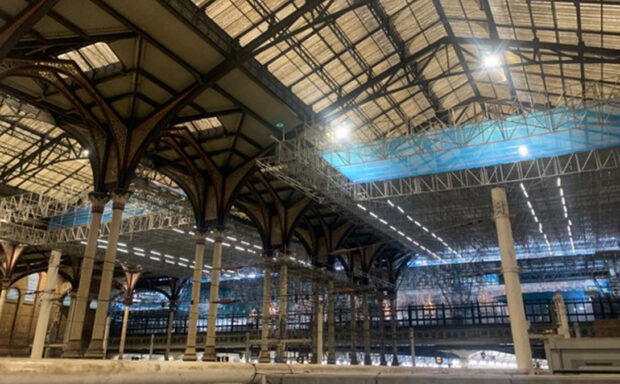

This month, we effectively brought London and South Wales closer than ever by completing the electrification of the Severn Tunnel. It means that for the first time, an electric railway runs all the way from Cardiff and Newport to London Paddington.

Electrification has resulted in thousands of extra seats, more frequent services and quicker and greener journeys for passengers as they travel to and from south Wales on train operator GWR’s Intercity Express Trains.

Mark Langman, managing director of Network Rail’s Wales and Western region, said: “Electrification has reduced journey times between south Wales and London by as much as 15 minutes and provided an additional 15,000 weekday seats compared with a year ago, with the possibility of further increasing the number of services and seats from south Wales in the future.

“It has been a hugely complex task to electrify the tunnel but I’m thrilled that the final piece of the puzzle is now complete.

“I would like to thank passengers and lineside neighbours for their patience over the past decade as we worked to deliver the transformation of this vital railway and am pleased that they will benefit from these improvements for years to come.”

Read more:

Isambard Kingdom Brunel and the Great Western Railway

Preserving railway history: five things saved by Network Rail