Between Folkestone and Dover lies an extraordinary stretch of railway.

It’s one of our main routes from Folkestone to London and runs on an active landslip – on a bed of chalk and gault clay.

Folkestone Warren is a designated Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) and in Europe is comparable with just one other place, in Italy, says Derek Butcher, route asset manager, geotechnics, drainage and off track on our South East route.

A hundred years ago, the railway here reopened after the worst landslip in the Warren’s history.

Watch this new film to see incredible historic images in 3D and find out more:

The Great Fall

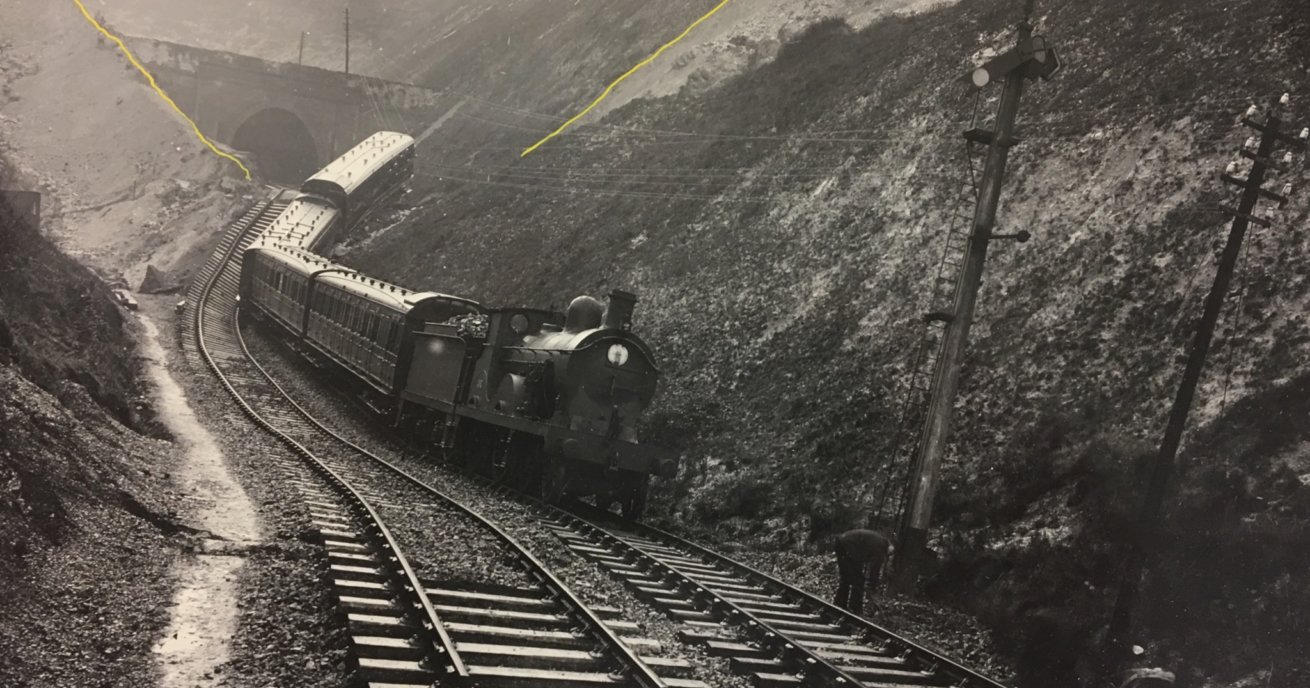

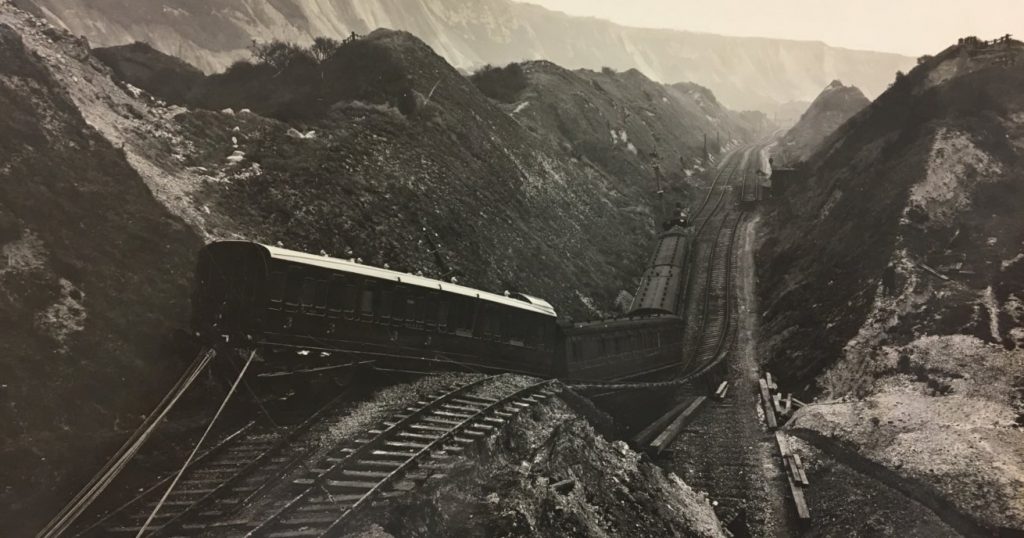

In December 1915, following weeks of heavy rain, The Great Fall shunted the railway line to Dover 50 metres towards the coastline and pushed 1.5 million cubic metres of chalk fell into the sea.

The line remained closed until 11 August 1919, the First World War having delayed its reopening.

Derek found original photographs of the incident in a filing cabinet while moving offices last year:

He said: “All landslides are activated by rainfall… [that location] has quite complex geology formed of chalk overlying clay. The water from the rainfall percolates through the chalk and sits on top of the clay and saturates it, and leads to landslips. The chalk can’t sit in a stable manner on the clay when it’s that wet.”

The kink in the line remains visible today, underscoring the severity of the incident.

‘The safest it’s ever been’

Landslips have been a major feature of the line since it opened in 1844. In 1877, two people died when part of the Martello Tunnel was destroyed. The line remained closed for three months afterwards.

The last major movement was recorded in 1939 but Derek said some ground movement had forced Network Rail to implement speed restrictions on the line in recent years. The need to take such precautions typically follows a very wet winter.

Today, the railway is “the safest it’s ever been” at Folkestone Warren, says Derek. We know this exceptional part of the network is particularly prone to such incidents so we have taken extra measures to monitor the landslip.

Derek said: “We typically get quite small movements, approximately 100 to 200 millimetres. We have minute-by-minute monitoring, not only of movement but also of weather as well.

“So we have a weather station down at Folkestone Warren, at the Warren Halt and that sends us back live information of wind speed, rainfall, temperature. And we can use that to try and correlate, for instance, rainfall and movement.”

Click on the gallery to see more images of Folkestone Warren:

We use light-detecting and ranging (LIDAR) technology, a laser scanning technique to record points on the landscape. The data helps us keep track of which locations are moving.

Remote condition monitoring (RCM) means engineers do not need to visit the location as often because it sends data electronically. Our teams can log on from the office or home on receipt of an alarm should the landslips movement exceed a threshold.

Derek said: “They can then decide what to do – for example, imposing a speed restriction or arranging a site visit to check all is well. This takes minutes to review the reading. The advantage of this approach is we can set the system to take readings when we want – for example, every second, minute, hour or day.”

Other techniques include boring holes in the ground to drain water, and building walls and other structures designed to stop the landslip from moving.

Meanwhile, Derek and his team regularly walk over locations at risk, comparing photographs to see whether the ground has moved.